Why You Can't Kickstart a Conference

Just yesterday, the seemingly promising Programming Languages Festival failed to raise enough funds on Kickstarter: its organizer, a YouTuber who goes by Context Free (I see what you did there) asked for $50,000 and raised $8,709. Given that he is a popular content creator and the speaker list was impressive (boasting prominent language designers and experts) I feel compelled to break down why this conference wasn’t viable in its current form. I also love offering programmers a glimpse into the messy business of running tech conferences, and this is a timely opportunity [1].

As a full-time indie organizer—who is currently doing okay for himself—I hesitated to write this essay because it could seem like I’m punching down. That said, I believe there are significant lessons to mine from this Kickstarter initiative: enough of them to be worth coming off as ruthless.

Indeed the tone I bring you today is bossy if not altogether shameless: forgive me, but you’re reading this from my personal blog! My hope is none of this puts you off too much and you come away feeling it was a worthy read.

A note to Context Free: there is biting commentary here; I trust you’re able to take it on the chin and I commend you for taking a risk. Hit me up if you want to talk shop.

Story Beats

Each lesson tends to carry personal anecdotes so it feels right to call them story beats. We have four in total:

- The need for a track record

- Conference operations: a black box

- The optics of seeking $50,000 upfront

- Ship vision first, polished product later

The Need for a Track Record

TL;DR: Unless you’re John Carmack or Nintendo you can’t launch a (profitable) conference without a track record.

When you’re still relatively unknown selling conference tickets becomes a formidable challenge.

I decided my first conference (2019) would have to be framed as a trial run: I dipped into my personal savings to cover the venue deposit, travel stipends for contributors journeying from afar, and so on. To attract attendees I went for heavily discounted access, with tickets priced at $50. I kept costs down and cut corners. I needed to accept that my first year would operate at a loss (fortunately we managed to break even.)

Long story short: it took until early last year (2022) for me to establish myself sufficiently as an organizer and transition to full-time status with Handmade Cities. These days I can pay for my rent in Seattle, groceries, and the occasional night out. At the time of writing, however, I can’t put any money away towards retirement.

It is my view that you need a strong spirit of risk-taking and a willingness to endure the long haul: doubly so if you’re indie. It’s actually unclear whether Context Free is looking to be independent or not? More on this later.

Conference Operations: A Black Box

TL;DR: Much like build systems, programmers may underestimate conference organizing because they only interact with the results.

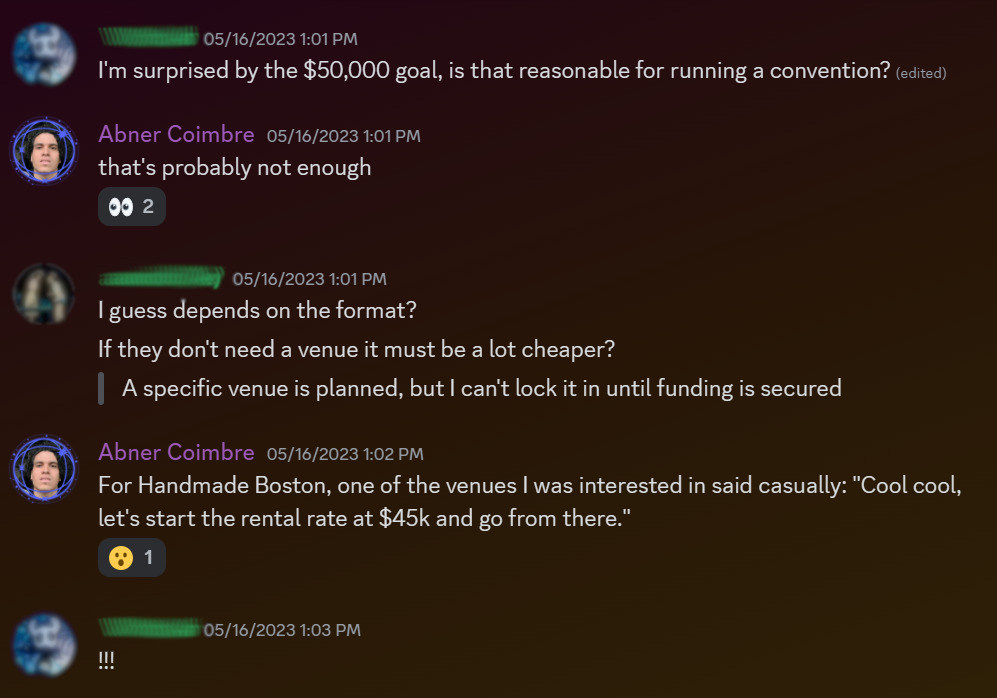

In the programming world it is difficult to prove to software engineers that build systems are actually hard to write from scratch. (Took me a while to get it!) Unfortunately, this exact phenomenon plagues the idea of running conferences too. For example, I personally understand how Context Free came up with the $50k figure in the Kickstarter but your audience might be confused:

This is because organizing a conference, like build systems, is deceptively complex. When I first started this career I was often asked why my conference couldn’t be free: after all, I’m “just sending a few emails” and “putting up some chairs,” right?!

One way to dazzle an audience with the truth is to show your battle scars:

In a recent podcast with Mr. 4th I got to explain how it’s an organizer’s job to competently solve problems dripping from the Inescapable Themes:

-

Theme #1: Unbounded Social Challenges - Who would willingly entrust you with the operation of a fancy venue in a major American city? Should you manage to secure such trust, congratulations—you now bear responsibility for the caterers, ushers, security guards, A/V technicians, janitors, booking agents, and the insurance company (because you better get insured.) The venue owners will hold you liable for any incidents transpiring within premises. I hope you haven’t forgotten about your speakers and your ticket holders, who rely on your organization. How about marketing to strangers so you can actually sell your tickets? WAIT YOU’RE HOSTING A JOB FAIR TOO? Good luck!

-

Theme #2: The Dilemma of Upfront Capital - If you want to lock in an attractive venue with the hottest travel dates be prepared to contend with established conferences which enjoy the backing of corporate sponsors. Most of them reserve a building a year ahead of time, so you’ll need to devise a way to steal a coveted spot from them. This process generally requires substantial sums of cash long before your ticket sales can even commence. Paying the speakers and your staff adds another layer of stress to an already demanding situation.

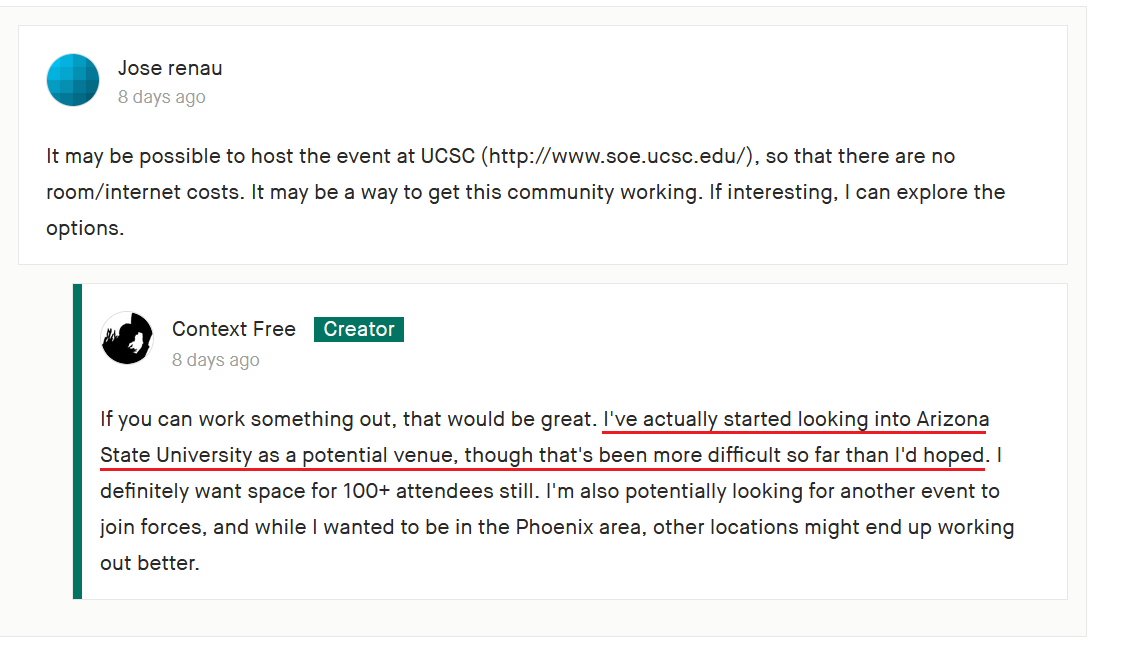

We can (understandably) see Context Free wrestling with Theme #2. I like his openness here:

All that said, there’s not enough advocacy in the world that could ever convince a large enough audience that operating a conference, big or small, is troublesome and expensive. We have to account for this reality rather than fight against it.

The Optics of Seeking $50,000 Upfront

TL;DR: The more you ask for upfront the more thorough your messaging needs to be.

Let’s say it again: the $50k ask from this Kickstarter was reasonable but due to the black box phenomenon this approach was all but guaranteed to fail. However, it may have had a fighting chance if it were not engulfed by some disastrous optics:

- Ambiguity surrounding independent status.

Are you an indie conference, or do you intend to seek out sponsors? This answer makes all the difference these days. You’ll get more backers if you confirm your independence.

Sponsorship deals of any kind are the reason the software industry is in the sorry shape it’s in. To the programmer not privy to backroom shenanigans this pronouncement may seem a little out there, but it’s the reality: tech conferences have the power to shape what we as software engineers focus on (a single talk at GDC can alter the trajectory of the game dev industry.) As of right now, nearly all events are sponsored by the tech giants.

Organizers who accept financial assistance from companies inevitably become beholden to their demands:

- Speaker proposals are denied

- Titles for talks get changed

- ‘Problematic’ PPT slides never see the light of day

- Your pamphlets are vetted one by one by some VP at Amazon

This is not a conspiracy theory—it’s the status quo. Why should we back anyone in their quest to become someone’s puppet? That seems like a pretty raw deal for the Kickstarter backer.

- Failing to mention ticket prices.

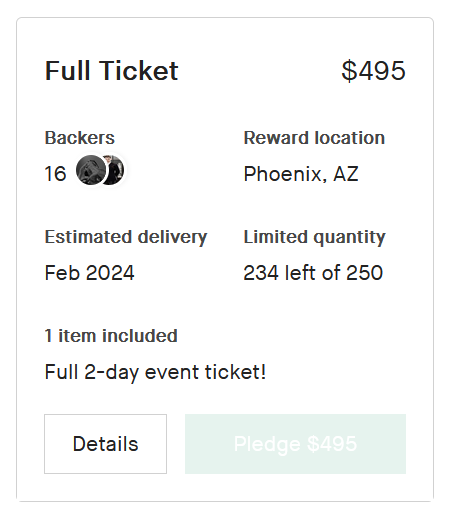

To be charitable towards Context Free it does seem like the ticket price was set to ~$500? I found it as a backer reward:

However, it is recommended to make ticket prices obvious right away and to clarify why you still need to sell tickets even after raising so much money! You don’t have to open up ALL your books (as a small business you have a right to closed books) but the more money you ask for the wiser it is to explain yourself.

- Weak organizing strategy.

The first hint that the Kickstarter’s organizing strategy wouldn’t inspire much confidence was when they made this claim:

More important than the topics are the speakers!

followed shortly by:

[…] there’s always a risk that some might not be able to make it

This warning was repeated again later in the campaign:

it’s possible some might not make it

in which case they said they would:

expect to find alternative speakers.

While I appreciate the transparency, I find myself perplexed. Why not have the speakers sign a contract? That’s how you state with confidence that your speakers will, without a doubt, attend. Yes life gets in the way but we can all agree that a legally-binding agreement (ideally with compensation / clawback provisions) suddenly eliminates these “life problems” in 99% of cases 🙂 The remaining 1% becomes an inconsequential risk not worth mentioning.

Note that with few exceptions, the topics themselves matter more than the individual speakers. An organizer must seek out a deep understanding of the industry zeitgeist, curate the most compelling topics, then decide the order of the talks and which speakers are most suited to give them. Finally you invite the speakers and negotiate what they should talk about: making sure they don’t deviate from your original vision unless their suggestions are clearly better.

P.S. To my speakers reading this: I love you all but I hope you agree that what is said should be valued higher than who is saying it.

- Failing to mention whether you intend to make a basic living from this.

There’s not much to add here: people are more willing to support you if they know this is how you’ll feed your family! If you have a well-paying job elsewhere, and this conference is a profit-making vehicle and not your livelihood, well… there’s nothing wrong with that but it’s only natural it will weaken your audience’s resolve.

Ship Vision First, Final Product Later

TL;DR: Ship Vision First, Final Product Later

My genuine suggestion to Context Free and to anyone in his shoes is to set their sights lower for their first conference. Make it a one-day thing instead of two. Rent a random hotel’s conference room—they sometimes fit a hundred people. Back in 2019 my venue costs remained under $10k. The event was nothing to write home about (although the talks were great): it was a rented hallway at the Seattle Center, with uncomfortable chairs, and the livestreaming broke down because I couldn’t afford the premium Internet. I still have nightmares on everything that went south.

Even though all I could ‘ship’ was an unpolished M.V.P. the vision behind the conference (read: organizing strategy) was STRONG. This leads us to my ultimate business advice for the aspiring organizer: ship your vision first and worry about polishing the product later.

Despite Handmade Seattle 2019 being less than stellar in terms of production, I still had the likes of Casey Muratori and John Carmack signal boosting the conference, because I made sure the mission statement was motivating enough for them to look past the warts. The audience mercifully granted me similar forgiveness.

This is what anyone needs first: make a sh*t ton of friends. Create a magical landing page, a fun trailer, and position yourself as an approachable figurehead. You must encode the organizing strategy into a speech you can recite a million different ways in a thousand different contexts. If you can nail that, go ahead and kick things off with a cheap venue and a skeleton crew; put everyone inside a tent for all I care.

The rest of it will catch up in a few years.

-Abner

Footnotes

[1] Hacker News thread here.